The cabbage borscht at United Bakers made me skip school. Served only on Fridays, I routinely dodged my morning classes to savour the sweet-and-sour soup with a hip mother who somehow believed that my grade twelve schedule was “flexible.”

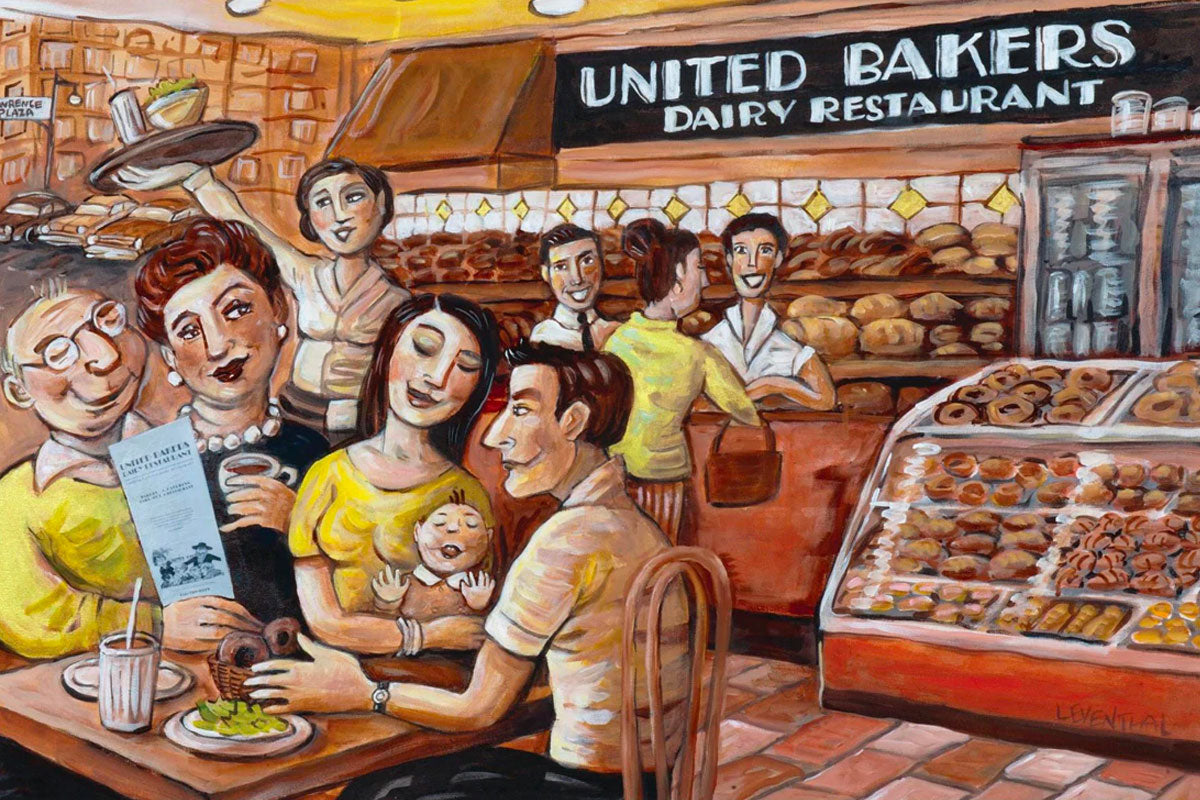

What I didn’t know then, and what most Torontonians don’t realize, is that the rich history of United Bakers Dairy Restaurant offers more than the comforts of potato kreplach and sweet gefilte fish. United Bakers (or United or UB, as it is also affectionately known) is Toronto’s oldest-running Jewish restaurant. A peek into the nearly one-hundred year past tells us as much about labour struggles and the history of Toronto as it does about Jewish immigration to Canada and dietary practices among Jews. From its modest lunch-counter beginnings downtown to its current location at Bathurst and Lawrence, United Bakers is a unique landmark on Toronto’s culinary and historic landscape.

As a dairy restaurant, United Bakers serves no meat and therefore loosely abides by kosher practices that involve the strict separation of meat and milk. Such dairy restaurants were common in the early- to mid-twentieth century across the Jewish world, and catered to the kosher or kosher-style tastes of immigrant Jews and their offspring.

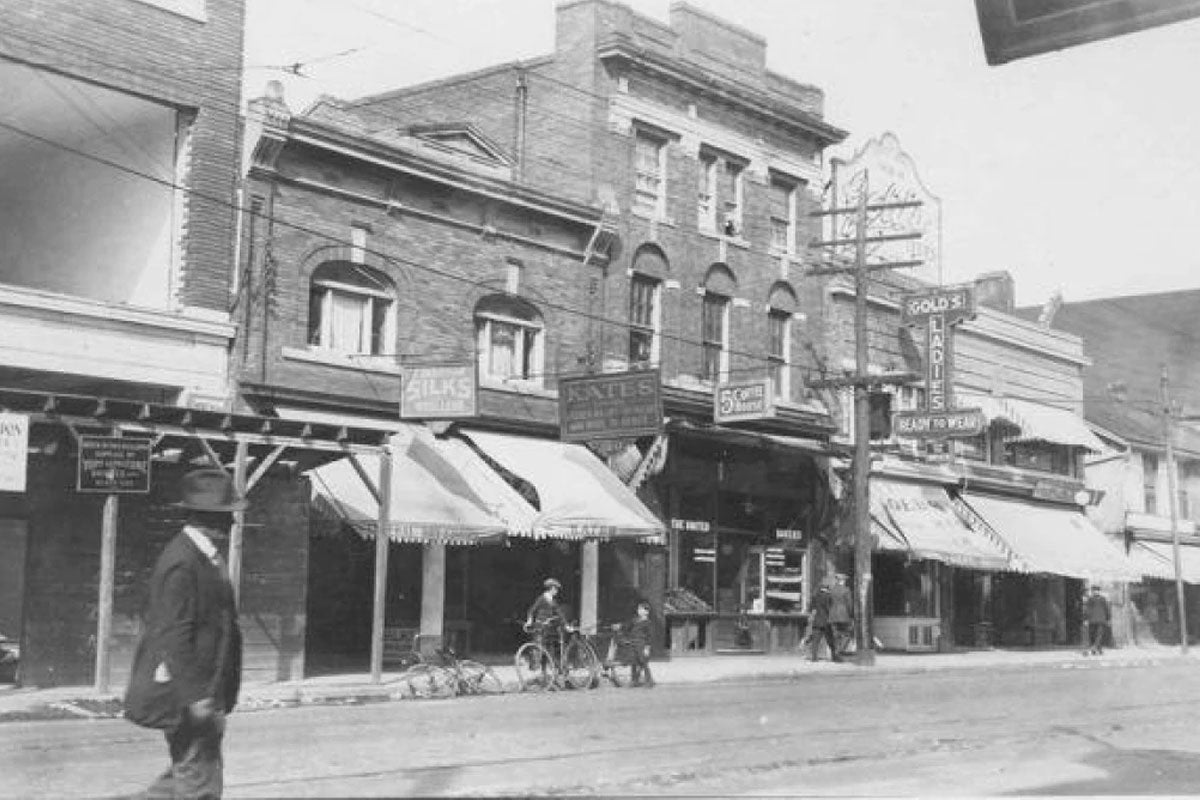

Many people still tell Ruthie Ladovsky, the third-generation owner along with her brother, Philip, that they had their first meal in Canada at United Bakers. “UB was their link to the new world,” Ruthie explains. That was back when the small coffee shop was located on Dundas Street at the corner of Bay (then known as Agnes and Teraulay Streets, respectively). The original location opened in 1912 – at the height of Jewish immigration to Canada – in the heart of the Ward, the

historic Jewish neighbourhood of Toronto.

In 1920, United Bakers followed the Jewish immigrant community to Spadina Avenue near Dundas. There it quickly became a beacon for fresh bagels and whitefish amidst the numerous Jewish storefronts, delicatessens, schools and synagogues. In the mid-1980s, the restaurant moved to its current midtown location.

But from its perch on Spadina, steps from the all-important Labour Lyceum, the de facto headquarters of the historic Jewish labour movement in Toronto, United Bakers served as a political and social centre for the nascent community while also serving affordable food to workers, artists and businessmen alike. An array of labour movements, from nationalist-oriented to the needle trades, characterized immigrant Jewish life in the first half of the twentieth century, and this no doubt spilled over at the tables of UB.

Ruthie recalls her father, Herman, a fixture at United Bakers until his death in 2002, telling her stories of heated debates and trade meetings in the early days: “The Labour Lyceum was two doors away from United Bakers, so it was a hub of labour activity. If anything was happening in world events, it was discussed at United Bakers. If you walked into United Bakers at six in the morning on Spadina Avenue, you would have people discussing major political things that [were] happening.”

In fact, Aaron Ladovsky, the original owner of United Bakers with his wife Sarah, in 1912 founded the Toronto chapter (Local 181) of the Bakers and Confectionery Workers International Union of America, an organization that advocated for collective rights among Jewish bakers and provided sick and death benefits. Aaron Ladvosky acted as founding president of this union, which was made up almost entirely of Jewish men.

Ladovsky was also instrumental in founding the Kielcer Society of Toronto in 1913, a community-based immigrant-aid association based on their hometown of Kielce, Poland, about halfway between Warsaw and Krakow. Such aid associations were common among immigrant Jews in the early years of the twentieth century and they provided everything from insurance and loans to burial services. Many Toronto Jews hail from Kielce, a typical feature of chain migration whereby more established friends and family helped facilitate the migration of loved ones to their new homes. Ladovsky remained a lifelong member of this organization, acting as president as late as 1948.

The local Kielce and Polish recipes no doubt add to the allure and popularity of the food at United Bakers. As Maria Balinska points out in her recently published book, The Bagel: A Surprising History of a Modest Bread (Yale: 2008), Poland was the historic bagelbasket of Europe. In fact, Aaron and his brother Lazar had trained as bakers in Poland (and Lazar became the baker at UB), but most of the food served was, and continues to be, based on Sarah’s original recipes. With the

exception of more recent additions to the menu like Greek salad and vegetarian lasagna, dishes such as herring with sour cream and kasha with bowties and onions rest comfortably on the east European palate.

Such food, of course, continues to appeal to many beyond the Jewish community looking for comfort food or a light meal with a dash of cultural exposure. Beginning with the infamous Lawrence Plaza parking lot – where drivers interpret stop signs as a mere suggestion – a meal at United Bakers is like no other. In fact, the Ladovskys are unique in continuing the tradition of their family’s eatery, unlike most historic Jewish dining establishments across North America that have all but disappeared or morphed beyond their humble European origins. For example, United Bakers’ New York City counterpart, Ratner’s, a dairy restaurant known for its legendary cheese blintzes, sadly closed its doors in 2002.

Besides United Bakers, the venerable Harbord Bakery, though not a sit-down eatery, remains an exception to this rule as the owners helm the downtown rugelach realm. Like the Ladovskys, the Kosowers have been following the same family recipes for decades, still churning out their ethereal apple cakes and prize-worthy challahs. These institutions persist and continue to succeed even though their devoted clientele has evolved, and despite the changed interests and demographics of the Jewish community. On the other hand, Caplansky’s might be bucking this trend with this new deli’s unselfconscious ode to old-fashioned Jewish cuisine in the form of smoked meat, knishes, and even an original take on cabbage borscht.

But nothing beats the daily lunch-rush schmooze-fest of kisses and kreplach at United Bakers. As for me, I’m just glad the cabbage soup is on the menu only on Fridays. Otherwise I would never have graduated high school.

United Bakers Dairy Restaurant

506 Lawrence Ave. West (Lawrence Plaza)

(416) 789-0519

Canadian writer Lara Rabinovitch hails from a long line of foodies. Currently a PhD student at New York University in modern Jewish history, Lara also serves as managing editor of Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures (www.cuizine.mcgill.ca).

– From Edible Toronto