In the Beginning...

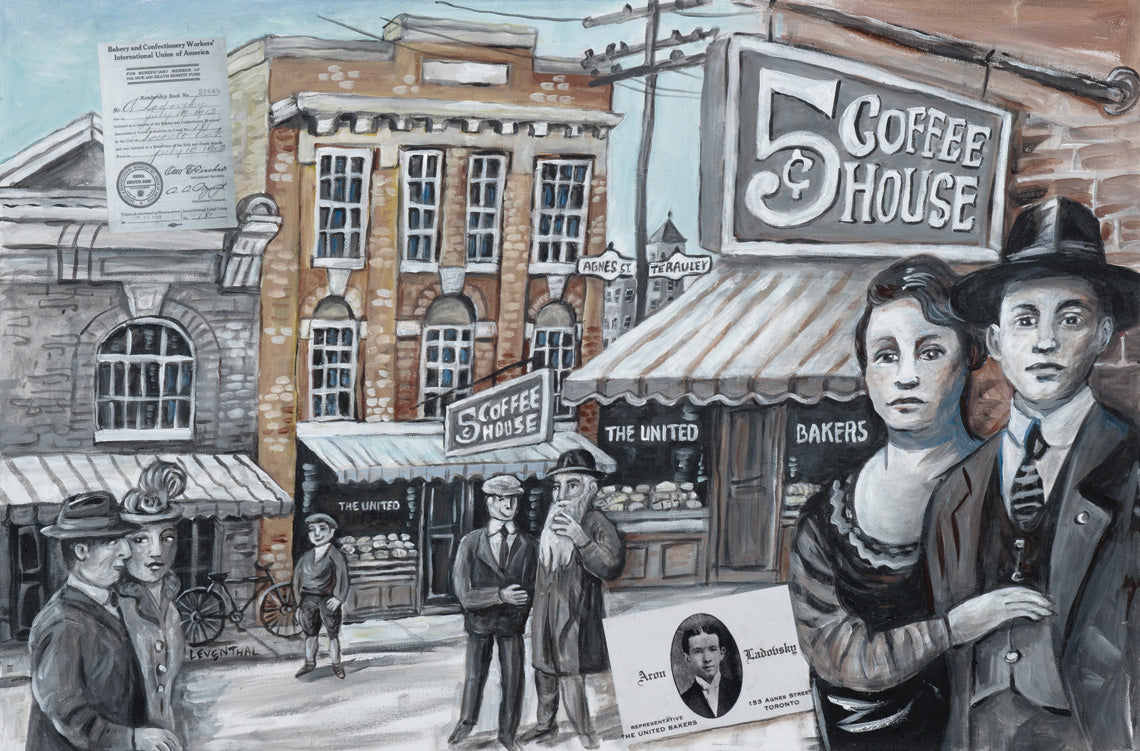

In 1912, a young couple from Kielce opened a bakery/coffee shop in downtown Toronto. Their plan was simple: to recapture the flavours of the life they had left behind in Poland, and to make a living here in Canada. They rented a storefront at 156 Agnes Street in what was then the heart of Jewish life, an area known as the Ward, and hung out a sign that read “5 cent Coffee House”. They called their new business THE UNITED BAKERS.

The Ladovskys began selling breads and dairy meals prepared on the premises, and their shop soon became popular. But could they have imagined that the same business they founded in 1912 would still be around to welcome customers through its doors one hundred years later? After over a century of continuous operation, UNITED BAKERS has carved a niche of its own in the story of Jewish life in Toronto. Having long ago become an historical landmark connecting the past with the present, the restaurant continues to enjoy a double identity as a place to eat and a place to meet. For many families and friends it remains an oasis of stability in our ever-changing city. This website is a sampling of the UB story: one version of a story that belongs to us all.

Aaron Ladovsky arrived in Canada in 1906, from Kielce. He was eighteen years old and single. In 1911, he married a girl named Sarah Eichler, also from his own home town. Both husband and wife maintained a strong connection to their Polish roots throughout their lives. The following year they had twin sons Samuel and Herman, the same year that they opened their coffee shop.

Coming from a family known for its baking and a country that was the historic bagel basket of Europe, Aaron was well prepared for the bakery business. Sarah brought in recipes for the foods from back home. In those early days, the coffee shops provided islands of familiarity amidst the swirling bustle of commercial life on the street. The sign in their window read “Quick Lunch”, and United Bakers quickly became a popular destination in the Ward. The patrons, all new immigrants, were a mix of those who had been in Canada long enough to become established and others who had just arrived. Yiddish was the language they spoke, though some English could be heard. The languages may have straddled both worlds, but the food they served was straight from the past: simple, country-style Polish cooking, with the emphasis on delicious and filling, comfort foods that would remind them of home.

The recipes used the basic vegetables they had been raised with – peas, beans, onions, carrots, cabbage, potatoes – peeled, chopped, diced and cooked slowly, until the aromas and flavours that connected them to their past were coaxed from the pot – often enhanced with a pinch of ‘secret’ ingredients like parsnip or paprika and always with a little sugar. Many a newcomer to Toronto enjoyed his first meal at United Bakers. From the start, United Bakers was a haven of stability in a turbulent new world.

At the time thousands of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe were arriving in Canada. The Jewish community was growing apace, and signs of expansion were everywhere. Across the street from the shop was the Lyric, Toronto’s first Yiddish theatre; a few doors along was the three-storey Terauley Street Synagogue.

Sarah worked alongside Aaron at the store, while their twin sons attended public school, first Hester Howe Public School on Elizabeth St and later Lord Landsdowne Public School - and cheder at the Kielcer shul. The Kielcer community of Toronto was also growing quickly. With new immigrants working tirelessly to bring over other members of their families, the phenomenon known as ‘chain migration’ was in full-swing. Many families depended for extra support on private societies usually consisting of people from the same district back home. These organizations would provide insurance, emergency loans, sick benefits, as well as sponsor cultural events and even annual picnics. Aaron Ladovsky became the first president of the Kielcer Sick Benefit Society of Toronto in 1913. He considered his connection to his Kielcer roots so important that in 1927 he embarked on a steamship and returned to Poland to meet with landsleit (fellow countrymen), bringing with him greetings, monetary support from new Torontonians for families back home, and, most importantly, encouragement to others considering the big move.

Ladovsky assured them that Toronto had much to offer for Jews, and for his efforts he earned the reputation as the “tate fun Kielcer” -- a godfather in the most benign sense. Aaron also was active in founding the Toronto chapter, Local 181, of the Bakery and Confectionery Workers’ International Union of America, a chapter made up almost entirely of Yiddish speaking Jewish men. The world of our grandparents was deeply infused with Yiddish culture. Many had strong political associations with the Labour movement. Such passionately felt connections naturally spilled over onto the tables of United Bakers, where politics and culture, social movements and scenes from the latest Yiddish theatre production, poetry, propaganda, and the ever-changing news of the day would be endlessly dissected and discussed – over a bowl of soup, a bagel, or a cup of tea, sweetened with a sugar cube or two.

Those who crossed the ocean running from poverty and those looking for a new start will happily tell you that UB was the place that would make sure that you had a hot meal regardless of your ability to pay.” -- Susan Jackson

Aaron Ladovsky, 1911

156 Agnes St. (currently 116 Dundas St. West)

Sarah Eichler marries Aaron Ladovsky 1911

Aron Ladovsky’s First Business Card

Hester Howe Public School Grade 3, 1919 (Herman 2nd row from top third from left, Sam top row, 3rd from right)

Aaron Ladovsky (bottom right) with members of the Kielcer society

Aaron in Kielce 1927 (Aaron in centre with hat meeting with Sarah’s three sisters and their families)

Spadina - The Early Years (1920 - 1955)

Immigration from Europe continued to increase. With the beginning of construction for the hospitals on University Avenue, the Ward was becoming too small to accommodate all the new arrivals. A different Avenue – Spadina – emerged as the new centre of Jewish life downtown. In 1920, United Bakers joined the flow, moving west to 338 Spadina Avenue, near Dundas Street. The new premises included plenty of window space to display buns and bagels. Inside were long wooden tables for serving breakfasts and a brick oven for the nightly baking.

Once again the Ladovskys found themselves punkt at the centre of Jewish Toronto, equidistant from the bustling carts of Kensington Market and the popular stage at the Strand theatre, where thespians, comedians, singers and dancers played to sell-out crowds, all in Yiddish. The neighbourhood boasted numerous synagogues, including the Bellevue and the Minsker shuls, both still open for services to this day.

Life on the Avenue was vibrant, and the restaurant became a magnet attracting customers from the clothing factories and the many small shops along Spadina. Itinerant businessmen in town for a few days would be directed to “Ladovsky’s” if they were looking for a good place to eat. Operating the restaurant was a family affair: Aaron’s brother Luzer arrived from Poland in 1924 to join in as a baker. His wife Rose became a waitress in the restaurant together with Sarah’s niece, also named Rosie. A third girl was hired as a waitress a year later. Her name, coincidentally, was Rosie.

Meanwhile, Herman and Sam, now in their teens, delivered fresh bread and hot buns all over the neighbourhood by horse and cart. Family legend holds that this horse was invited to perform a walk-on at the nearby Strand Theatre one winter evening when the regular equine was feeling indisposed.

With the Labour Lyceum, headquarters of the Jewish Labour movement, right next door, United Bakers continued to be a hub for political and social activity. It was the kind of place that suited nearly everybody– factory owners and their workers, businessmen, professionals, artists, people from all walks of life, rich and poor alike. Aaron had a particular love of the Yiddish language (which he spoke with eloquence), and would always welcome Yiddish writers and poets to enjoy dinner on the house.

Payment was based on the honor system: you came to the cash register, recited what you’d eaten, and were charged accordingly. Not a few times a patron who was short on funds would eat for free. And often, a salesman would be given a pack of provisions gratis to take on his journeys. The Ladovskys turned no one away, trusting that those they quietly assisted would one day provide for themselves and for others, too.

Soon Herman was working alongside his parents in the store. His twin brother Sam had married and was working with his wife’s family in their hotel business. When World War II broke out Herm enlisted and was stationed overseas as a technical assistant with the Canadian Army Show. He became fast friends with soon-to-be-famous comedians Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster.

Returning to Toronto after the war, Herman rejoined his parents at United Bakers. His mother Sarah, doing what Jewish mothers have always done well, contrived to have him meet a young nurse from Regina about whom she had heard good reports, a certain Dora Maclin. Sarah concocted a reason to send her son on an errand to the medical office where Dora worked. Herman and Dora were married in 1947. By 1951 they had three children.

Aaron, Sara and Luzer, 1924

Rosie Ladowsky on V E Day, 1945

Spadina - The Later Years (1956-1986)

While United Bakers grew ever more popular, the Ladovskys clung tenaciously to their format as a dairy restaurant. The laws of kashruth require milchick (dairy) & fleishich (meat) to be kept separate. Serving only dairy foods in the restaurant would allow even the more observant to dine comfortably. The dairy-only kitchen at “United” acquired an enviable reputation for many of the foods that remain staples on the menu even today.

By the 1950s United had evolved, becoming only a restaurant, and offering baked goods for take-out. Around that time the store underwent a complete make-over. The giant bake oven that had been built in 1920, no longer in use, was bricked up. Gone were the dark wood display shelves, the cane-back chairs and the old wooden tables, all replaced by a Formica counter in pink with a dozen twirling luncheonette stools on shiny chrome bases. Customers perched on their stools could now watch as their eggs were cooked before them on open burners, beside an array of stainless steel refrigeration with sliding glass window-doors and a large metal coffee urn with an easy-flow spigot.

Behind this, the walls were covered with stainless steel – as modern as a jet airplane but easier to wipe down and keep clean. The original pressed tin ceiling remained, but it was stripped of its traditional ceiling fans. These were replaced by a newly-fashionable system called Air Conditioning, a feature considered important enough to warrant a mention on the back cover of the menu. On the front cover, the tag line read: Delightfully Delicious Dairy Dishes / Fragrant Fish from Far & Near.

In April 1960, Aaron Ladovsky passed away. While he was recognized as the owner of a business that had grown to occupy a spot in the hearts of many, he was also remembered as a leader in his community: in the words of J.B. Salsberg, a popular politican and writer, Aaron was “a true ‘Yiddisher folksmensch’ ”Herman, now in his forties, had already taken over the day-to-day operation of the restaurant. With his father’s passing, he became the sole proprietor. Hymie, as he was fondly known, had just the “right stuff” for this kind of business, to the manor born as a restaurateur.

At a quarter to six each morning he would arrive to open the doors, to let in Mary (his cook for thirty years, with whom he mainly communicated by gesture and paycheque, since his command of Polish and hers of English were equally tenuous) and to prepare for the day ahead. Most days, before the sun had risen, a dozen regular customers were already settled in front of their steaming coffees, flipping through the pages of the Toronto Telegram and exchanging comments over the news of the day.

The staff were as regular as the customers. For decades, Herman employed the same three waitresses, along with one Polish cook and one strong fellow in the back to serve as cook’s helper and wash all the dishes. Herman brought his cousin Morris Lefko into the business. A scholarly and pious man who never appeared without his trademark bowtie, “Moishe” was a fixture at the register.

Herman’s daily presence contributed much to the ongoing success of United Bakers. He ran his business with a firm but generous hand, acknowledging nearly every customer with a smile. He always found time to exchange a greeting or a joke, to make each person feel comfortable. In fact, United Bakers seemed to belong to the customers.

Through the 50’s, the 60’, & the 70’s United Bakers continued to be a popular eatery on the Avenue. Always a busy place, the atmosphere of bustle and liveliness had broad appeal. Tables were never reserved. You took a seat wherever one was available. This made for some interesting groupings, bosses sitting at the table with their employees, surgeons joining fur-cutters for lunch, and occasionally a judge perched on a stool at the counter next to someone whose means of employment might charitably be called ‘questionable’. For students attending university downtown, here was a comfortable haven where they could enjoy a meal and shmooze with the colorful clientele. Always there was a contingent whose heavy East European accents betrayed their roots, and who still gravitated towards United, drawn in by the incomparable tastes of home. Politicians and prominent public servants visited the restaurant frequently, as did many local and international celebrities.

Journalists and writers, artists, musicians, performers, intellectuals, academics – all found their way down to United on a semi-regular basis to refresh their own roots, and to enjoy the atmosphere.

Whether coming in for some of Herman’s freshly scrambled eggs, or a bowl of bananas with sour cream, an eier kuchel, a muhn cookie, sometimes just for a bagel - the experience itself was the treat. Down the street Sammy Taft sold hats to the rich and famous. Shopsy’s sold hot dogs to nearly everybody. But United was in a class of its own. More than a coffee shop, or even a quick lunch, it became everybody’s home away from home. Herman’s hard work and his charm continued to keep the regulars returning as well as attracting a steady flow of newcomers, as he carried the tradition forward into the latter half of the century.

By the mid 1970’s, two of Herman’s children, Philip and Ruthie had joined the business, carrying on the spirit of hospitality and warmth that United Bakers was known for. Their first innovation was to open Sundays for breakfast, something Herman initially opposed, since downtown was generally quiet on a Sunday. He was quickly brought around, when, by the end of the first month, customers were lining up out the door. Nonetheless the neighborhood was experiencing a dramatic transformation. New waves of immigrants, mainly from the Far East, were buying up buildings and businesses all along Spadina. Kensington Market, once known as “the Jewish market”, came to reflect a new, multicultural Toronto.

United Bakers continued to serve the downtown regulars, but downtown itself was changing. The needle trade was dwindling, jobbers were moving off the Avenue, and much of the manufacturing was being transferred offshore. The general appearance of the Avenue had changed. New grocery stores took to spreading their fresh produce and wares out along the sidewalk. But the most serious inhibitor to running into United for a “quick lunch” was the absence of nearby parking.

In October 1984 the Ladovskys assumed the lease of a restaurant space in a plaza in North York with lots of parking. The location could hardly have been a better fit. First built in 1951, Lawrence Plaza was a relatively new type of shopping centre called a ‘strip plaza’, where customers could park near the store they were headed for without having to enter a covered mall. This gave it a kind of “downtown” feeling. Lawrence Plaza had the added advantage of being situated right at the heart of Toronto’s Jewish community in the 1980’s. The same customers who had frequented the United downtown for decades could now join their families for lunch at the new United Bakers “Uptown”.

With no more advertising than a sign in the window that read “under new management”, United Bakers Uptown attracted a line-up from the first lunchtime. Two years later, in the summer of 1986, the Ladovskys formally closed their downtown location, bidding farewell to a place that had witnessed so much of the growth and maturation of Toronto’s Jewish community. Many felt that leaving Spadina was the end of an era... fortunately they found a convivial atmosphere to keep the memories and the tradition alive at – where else? —the new United Bakers at Lawrence Plaza.

Lawrence Plaza - Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Much like that first move from Agnes & Terauley onto Spadina some 64 years earlier, the restaurant’s relocation once again mirrored the continuing story of Jewish Toronto as it expanded and grew. With their dedicated staff, some of whom came up from downtown, the Ladovskys carried on selling baked goods and an even wider variety of prepared dairy foods. New items found their way onto the menu, including everybody’s favourite Greek salad, and signature specialties remained as well, including the perennially popular split-pea soup.

Six months after opening at Lawrence Plaza, UB (as the new crowd took to calling it) underwent the first of two major renovations: a servers’ station was removed from the centre of the restaurant underneath the mirrors thus opening up the whole space for everybody to see and to be seen. This was more the kind of shared public space UB had always been.

Herman continued to be a beloved presence in the restaurant. Every day he could be found at ‘his’ table at the back of the dining room, ready to greet friends and customers with jokes and stories from the past. He watched with pride as a whole new generation of children discovered the pleasures of the same split pea soup he had grown up with. When he passed away in 2002, a few months after 9/11, he left behind a world that had changed nearly beyond recognition from the one his parents inhabited. Like his father before him, his legacy included a successful business and a well-respected name.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, one hundred years after Aaron opened his small bakery on Agnes Street, thousands of Torontonians continue to frequent the Ladovskys’ restaurant on a regular basis. It’s that kind of place – a restaurant where you can come and enjoy a breakfast, and come back for lunch and even dinner and find enough variety on the menu and enough comfort in the milieu to make each visit a pleasure. For many a young mother, bringing her new infant in to UB is a rite of passage, especially since more than a few of those becoming parents today took their own first steps in this same place. Their own parents, having become grandparents, can be seen kvelling as the cycle of generations continues, and as the Ladovsky family, with pride and with love, prepares United Bakers for its next hundred years.

Ruthie, Herman, and Philip Ladovsky c. 1997